Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: How ACT Can Help You Solve Problems and Improve Your Life

February 11, 2018

Categories: Psychology

I’ve been getting into a counseling approach called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; pronounced as one word, not “eh-see-tee”). ACT has helped me to effectively deal with problems in my own life, so I thought I would give a brief primer on the approach to see if it can help you as well.

Situating ACT in the Counseling Landscape

First, I want to give some background about ACT and where it fits into the counseling landscape. ACT is a type of behavior therapy, so a big part of the approach involves trying to change behaviors that are causing problems in your life. (ACT talks about this process as committed action in line with your values. More on that later.)

ACT is one of the third-wave behavior therapies, so it is a bit different from traditional behavior therapy. The first wave of behavior therapies focused on the theory of behaviorism, and used principles such as reinforcement, reward, and punishment to change behavior. The second wave of behavior therapies focused on cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), which targeted both overt behavior as well as one’s thoughts, which were thought to undergird one’s feelings and behaviors.

As a third-wave behavior therapy, ACT still incorporates a lot of traditional behavioral techniques to change behavior. And similar to CBT, ACT also views thoughts as important, although ACT deals with thoughts in a different manner than CBT.

The Key Difference Between ACT and CBT

Many people who are interested in psychology are familiar with CBT, which is probably the most well-known and researched form of therapy. Briefly, CBT says that our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are closely connected. In order to address a psychological problem (such as anxiety or depression), CBT tries to target the problematic thoughts and behaviors that are associated with the distressing feelings. For example, if a person is struggling with anxiety around flying, a CBT therapist might try to help the client change their problematic thoughts (e.g., flying on an airplane is dangerous) and behaviors (e.g., avoidance of air travel) that are connected to their fear of flying. If a person is struggling with depression, the CBT therapist would help the client change problematic thoughts (e.g., I’m worthless) and behaviors (e.g., staying in bed all day) that are connected to the feelings of depression.

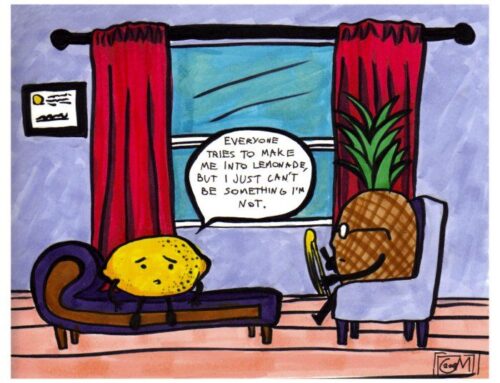

The key difference between ACT and CBT has to do with how we deal with problematic thoughts. In CBT, the goal is to evaluate the evidence about whether the thought is true or false, and try to change the problematic thought to become more balanced and healthy. ACT, however, says that changing a thought is really difficult, because the thought is often based in our history and experiences. Furthermore, because of how language works, the process of trying to change or modify a thought can backfire and cause the thought to become more entrenched.

For a simple example of this, take the next 5 minutes and try NOT to think about a banana. Don’t picture a banana in your head and don’t think about what a banana tastes like. Whatever you do, don’t think about a banana. (Stop reading this post and actually try this banana exercise for the next 5 minutes.)

If you’re like most people, during this exercise, you actually thought more about bananas than you usually do. The banana example is harmless, but the same principle applies if you are dealing with a psychological problem. If you spend a lot of time and energy trying not to be anxious or depressed, you might paradoxically find that your anxiety or depression gets worse.

Instead of trying to change or modify difficult thoughts, ACT encourages folks to work on accepting their internal experiences, even if they are painful or difficult.

The 6 Key Components of ACT

There are 6 key components of ACT. In this next section, I want to talk about each component briefly, and give an example of an activity you can try to apply ACT in your own life. Before I get into the 6 components, however, I want you to think about a psychological problem you are dealing with right now. Try to think of the problem that is causing you the most pain. Throughout the rest of this post, keep this problem in mind as you read the material and work through the exercises.

- Acceptance. I’ve already talked a little bit about the principle of acceptance when I talked about the key difference between ACT and CBT. When you experience a painful thought, feeling, or bodily sensation, the natural tendency is to do something to avoid what you are experiencing. ACT says that, paradoxically, this pull to change or avoid your internal experience can actually make your problem worse. Maybe you can relate when you think about the problem you are dealing with. You might be anxious, AND angry/frustrated that you haven’t been successful at reducing your anxiety. This anger/frustration about your anxiety makes you feel even worse. The alternative to avoidance is to be willing to experience your difficult thought, feeling, or bodily sensation, just as it is, without trying to get rid of it. As an exercise, imagine that your difficult internal experience is an unwanted houseguest at a party you are hosting. You don’t want to let the guest in, but they keep banging on the front door. Finally, you let them into your house, but they are being obnoxious, spilling drinks and talking loudly. You try to lock them in the study, but they get out and return to the party. You walk them back to the study and try to lock them in again, but they escape and return to the party again. If you keep trying to get rid of the houseguest, you will miss your own party. This is similar to the task of trying to get rid of an unwanted internal experience. You can try all you want to avoid the experience, but you might miss out on your own life in the process. The alternative is to accept the experience (i.e., let the unwanted houseguest into the party) and live your life (i.e., enjoy the party) as best you can.

- Cognitive defusion. The opposite of cognitive defusion (which is a made-up word) is cognitive fusion. Cognitive fusion means that we are fused, or connected with, our thoughts. We believe our thoughts as if they are literally true. We have thoughts, and we believe that our thoughts cause certain things to happen in our life. We might believe our depression, for example, is caused by our beliefs that we are unlovable. We might believe our anxiety is caused by our thoughts about the dangerousness of the airplane. We often come up with elaborate stories in our heads about our psychological problems and how they developed. When we are cognitively fused, we experience our thoughts as literally true, and they run our lives, whether they are helpful to us or not. One of the key principles of ACT is that our thoughts are just thoughts—they aren’t necessarily true and we don’t have to let them dictate our actions and behaviors. One interesting exercise to help you with the process of cognitive defusion is to think about the word “milk.” What comes to mind? For many of us, we can picture a glass of milk, and perhaps even taste milk in our mind. We might think about cereal or cookies. We might even have a negative reaction or feel sick (if we are lactose intolerant, for example). All of this happens just by reading these words and thinking about the word milk. Next say the word “milk” out loud repeatedly for 30-45 seconds. Just keep saying the word out loud, as fast as you can. For many people, they start to lose focus on the meaning of the word in their minds, and instead focus on other aspects of the word (e.g., how the word sounds, how the muscles of their mouth feel as they say the word, etc.). This is an example of cognitive defusion—the word begins to lose its literal meaning, and we can see the word for what it is—just a group of sounds put together that have symbolic meaning. The same exercise can be done with your painful thought—say it out loud repeatedly for 30-45 seconds. See if you can defuse from the literal meaning of the thought.

- Self-as-context. The opposite of self-as-context is self-as-content. Put simply, we tend to make up stories about ourselves (i.e., the content), and believe they are true. For example, I have a story about myself that I struggle with perfectionism because when I was growing up, I was anxious about being a failure and not being good enough. This showed up in a variety of areas of my life, such as school (e.g., feeling badly about myself when I would get a question wrong on a test), relationships (e.g., feeling badly about myself for being overweight and struggling with dating), and even religion (e.g., feeling badly about myself when I would do something I considered a “sin”). Then I developed a rigid view of what it meant to be good or successful (i.e., perfectionism) in order to protect myself from the negative feelings that came with feeling like a failure and not good enough. I’ve told this story to myself in my head many times, so now it feels true to me. But at its core, it’s a story that I made up about myself to make sense of my experiences. The problem is that because the story feels true to me, it influences my future (e.g., feeling badly about myself when I’m less than perfect, holding unrealistic standards for myself and others). Being enmeshed in the content of my stories keeps me stuck. It doesn’t allow me to make different choices moving forward. My stories about myself affect how I perceive my future experiences. The alternative is to see the self-as-context. In this way, I separate my sense of self from the stories I tell about myself. These stories are thoughts that I am having, but they don’t make up the core of who I am. As an exercise, think about yourself as a chess board. There are several pieces on the board, which represent your thoughts and stories about yourself. Some of these stories may be positive (e.g., I’m a smart person) and others may be negative (e.g., I struggle with anxiety). But the pieces are not you. The board is you. You experience a thought (separate from yourself) just as the chess board holds the queen or the pawns (which are separate from the board).

- Contact with the present moment. ACT encourages us to focus on connecting with the present moment as much as possible. Often when we are struggling, we get caught up in the past or the future. If are stuck in the past, we might feel regret over past mistakes or failures, or spend a lot of time trying to figure out “why” we are struggling with a particular problem. If we are stuck in the future, we might experience a lot of anxiety worrying about what might come to pass tomorrow, the next day, or ten years from now. Either way, we miss out on our actual life, which is lived in the present, moment by moment. One helpful way to improve our contact with the present moment is to practice mindfulness. Right where you are, close your eyes and focus on your breath. Breathe in slowly, hold your breath for two seconds, and then breathe out slowly. Repeat this for five minutes. If a thought, feeling, or sensation comes up, notice it, let it go, and return your focus to your breath. Similarly, throughout your day, if you find your mind wandering to the past or the future, notice your thought (e.g., “Hello mind, I see that you have traveled to the past again!”) and bring your attention to what you are doing in the present moment.

- Values. Values are huge in ACT. The reason we try to accept and defuse from our thoughts isn’t for the sake of just accepting and defusing. We work on acceptance and defusion so that we can be free to behave in ways that are consistent with our values. Values involve what is most important to us in life. Values help clarify what it would look like for us to live a meaningful life. When we are living a life in accordance with our values, we are alive, engaged, and purposeful. I want to mention two key points when it comes to identifying our values. First, values are different from goals. Goals are things that we are working toward and can be accomplished and completed. Values are deeper and involve ongoing committed action over the course of your entire life. For example, losing 20 pounds is a goal. Being a physically healthy person is a value. Publishing a book is a goal. Producing meaningful work is a value. Second, values must be freely chosen. Be careful of adopting values just because a person in authority (e.g., parent) or cultural/religious group says the value is important. Be honest with yourself and test whether the value leads you toward a life that is alive, engaged, and purposeful. If it does not, you may be in a state of compliance—it might not truly be your own value. Have the courage to discover and live your own values. Here’s an exercise to help identify your core values. Imagine that several years have passed, and you have died. You are lying in your coffin at your funeral, and it is time for your closest family and friends to get up and say a few words about your life. Think about what you hope they would say. Actually write down what you hope they would say about you. After writing down your eulogy, reflect on what you wrote. What key themes stood out to you? What do these themes say about your core values? Try to identify 3 core values that are most important to you.

- Committed action. ACT prioritizes committed action in the service of your values. In other words, when you look at your actions and behaviors every day, do they reflect what you consider to be most important? Or are you doing a lot of things that aren’t actually contributing to a meaningful life? Again, the purpose of acceptance and defusion isn’t just getting to the place of acceptance and defusion—it’s so you have the freedom to engage in committed action in the service of your values. One key exercise here is to take stock of your actions and behaviors. Your daily planner is where the rubber meets the road. Write down everything you do for a week. How much time is spent on activities that are in service of your core values? How much time is spent on activities that are extraneous or outside your core values? What could you do this next week to tilt the balance of your time? Could you add one thing this week that is connected to your core values? Could you take away one thing this week that is outside your core values?

Discussion: What do you think of ACT? What rings true for you? What do you still have questions about? This week, see if you can work through the exercises for the 6 key components of ACT with your most painful psychological problem. Perhaps focus on one component per day. What came up for you as you worked through the exercises? Did you notice anything about your life? Did you feel a greater sense of vitality, freedom, and meaning?

Further Reading: If you want to learn more about ACT, here is a great book by Steven Hayes that is very easy to read and understand: Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life

Related Thoughts

4 Comments

Leave A Comment

Subscribe To My Newsletter

Join my mailing list to receive the latest blog posts.

Receive my e-book “The Mental Health Toolkit” for free when you subscribe.

Hey Josh, it’s been awhile since I’ve commended. I read your blog regularly and appreciate your thoughts, reflections, teachings. I found ACT very interesting and plan to get the book you recommended.

Thanks for your willingness to share yourself in the blog.

Thanks John! Yeah, I found ACT really interesting and helpful as well.

[…] Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), we call the process of locking into a thought “fusion.” Fusion basically means the bringing […]

[…] Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) takes a slightly different route. ACT says that changing thoughts is pretty tough to do, because we can’t really control our thoughts—they happen more or less automatically. Instead of trying to change our thoughts and feelings, ACT encourages us to accept them (even the problematic or painful ones). However, they do encourage us to take a closer look at the relationship between our thoughts and behaviors. Cognitive fusion occurs when our thoughts and behaviors are intertwined (e.g., I am feeling depressed, and my depression causes me to stay in bed all day). Cognitive defusion, on the other hand, is the process of separating our thoughts and behaviors (e.g., I am feeling depressed, but I can still get up, go to work, and call a friend). Cognitive defusion is generally associated with better mental health and well-being. […]